My new study (2014-16)

Young Europeans’ Political Identities

How they are constructed and what this tells us

On this page I give an overview of the project [pull down menu: Overview],

A brief description of my current and plans to extend this work. If you are interested in participating in my future plans, please don’t hesitate to contact me [pull down menu: Plans].

There are more details of the project with a summary of findings so far (outputs and you-tube lectures), on this page [pull down menu: Findings]

Ross, A. (1984). Developing political concepts and skills in the primary school. Educational Review, 36 (2), pp 131–139.

An early article, which although dated, offers some analysis if what young people (7-11) can be capable of in the sphere of political learning.

“Young children are capable of holding fairly sophisticated political concepts and of developing political skills, particularly if both are derived from the direct experiences of the child.” (p. 131)

“Children need first to describe and discuss their own personal experiences: the teacher’s role is to encourage everyone that their knowledge is a valid starting point for discussion … not necessarily to introduce new vocabulary to the child, but often to use children’s own expressions to help them clarify ideas. The teacher cannot ‘teach’ concepts by defining them: they are built up slowly by the child accumulating a battery of examples and beginning to note the similarities.” (p. 134)

Ross, A. (1987). Political Education in the primary school. In Clive Harber (Ed.), Political Education in Britain, pp 9-24. Lewes: Falmer.

A wide-ranging survey of the then current literature on political socialisation in this age group, with examples drawn from isolated examples of current practice in the UK.

The chapter “move[s] from the evidence that shows the political understandings that nearly all children show, and the undoubted political competence that some children can achieve, to consider in what curricular guise political education will probably occur in schools." (p 22)

Ross, A. (1988). The Social Subjects. In M. Clarkson (Ed), Emerging Issues in Primary Education, pp 207 – 222. Lewes: Falmer.

This analysis of the social subjects’ place in the curriculum was written in the months before the National Curriculum was announced, and offers an account of the ‘state of play’ at that critical juncture. It analyses the respective roles of the Local Education Authorities, the Schools Council, the Inspectorate and the schools in developing the social subjects – or perhaps the social sciences – as ‘synthesizers’, ‘restructuralists’ and ‘particularists’, particularly in the light of the rapidly changing ethnic diversity of schools at this time.

“The initiative [of the synthesizers] provoked a series of rejoinders, both from those who sought to reassert the primacy of traditional subject divisions, and from those who wanted to redefine the social subjects as a convenient way of developing social skills. As yet, these reconstructionists are ill-coordinated and have not put forward any strongly argued and practical counter-proposals: but there would probably be a fair-sized body of primary teachers who would respond to a call to reintroduce the traditional subjects, taught in a traditional manner.” (p 217)

Others “have defined their curriculum concerns in a manner that links them to the social sciences. This approach has strengthened the social science movement.” (p. 217)

Ross, A. (1993). The Subjects that Dare not Speak their Name. In R. Campbell (Ed), Breadth and Balance in the Primary Curriculum, pp 137 – 156. London: Falmer.

Five years later, and the social subjects had become covert fugitives from the regime of the National Curriculum. This essay was written as part of a Festschriften for Alan Blyth, a pioneer of social studies from 1945 till well after his retirement in 1985. As I note, not only had the ‘social subjects’ disappeared from the then formulations of the National Curriculum, but as had the word ‘society’ itself. A chart in this chapter (pp 139-141) shows how the primary school curriculum had been divided and labelled from 1967 to 1991.

“Most primary teachers have an intuitive, rather than a well-articulated, view of the social in the curriculum. Only a minority have the energy, the analysis, or indeed the courage, to weld a social studies curriculum out of the jigsaw of the National Curriculum’s foundation subject and the whole curriculum’s themes.” (p 153)

“Not only are the social subjects a necessary part of the whole curriculum, they are already available, in a pice-mean form, within the existing skeleton of the national and the whole curriculum. The only way of making them sufficiently explicit, and this achievable, will be to draw the disparate parts together, and offer this as something not only greater than its parts, but also simpler than its parts.” (p. 154)

Ross, A. (1995). The Rise and Fall of the Social Subjects in the Curriculum, in J. Ahier and A. Ross (Eds.), The Social Subjects in the Curriculum, pp 53-78. London: Falmer.

A review of the curricular changes in the social studies curriculum from the 1960 to the roll-out of the 1988 National Curriculum in England, that argues that it was essential to maintain a social studies dimension. The argument focuses on the primary and middle years of education, examining UK and international trends in the 70s and early 80s, and the attack on social studies from right-wing commentators in Thatcher’s Britain in the late 80s and early 90s.

“The social elements of the curriculum … changed radically with the imposition of the National Curriculum. One view might be that they were … disposed of, [through] ‘benign neglect’, then frozen out of discussion, and finally legislated into oblivion. A counter view might be that they were translated into other disciplines … by interested professionals acting in a subversive manner to colonise the new curriculum. But alternative might be that many of the themes and concerns that were hitherto located within the social parts of the curriculum were subtly reformulated and reintroduced … in the cross-curricular themes.” (p. 77)

Ross, A. (1995). The Whole Curriculum, the National Curriculum, and the Social Subjects. In J. Ahier and A. Ross (Eds), The Social Subjects in the Curriculum, pp 79 – 99. London: Falmer.

An analysis of the UK Government’s assertion that the ‘Whole Curriculum’ was broader and greater than the National Curriculum, and that cross-curricular themes would provide this. The documentation of these themes are analysed, and it is suggested that they largely were structured to develop a sense of individual responsibility among young people, rather than offer any broader social perspectives: the individual is made the author of their own misfortune. This is coupled to curriculum initiatives to ‘invent’ a national heritage.

“These elements do not simply offer a framework that mirrors the social experiences of our communities. They reorder the curriculum, so that children will learn more about their own individual obligations and responsibilities than about the social organizations that offer them rights. …The National Curriculum, and the Whole Curriculum that surrounds it, is an attempt to invent traditions that deny community, welfare and social action.” (p. 98)

Ross, A. and C. Roland-Levy (2003) Growing up politically in Europe Today. In C. Roland-Levy and A. Ross (Eds.) Political Learning and Citizenship in Europe, pp 1-16. Stoke on Trent: Trentham.

This was the third book in the CiCe series European Issues in Children’s Identity and Citizenship (8 volumes, between 2002 and 2008: see also A European Education, under Citizenship Education, below). In the introduction we draw attention to the construct of young peoples’ political identity, as taking place from an early age, and the way that this will be set among a range of identities.

“The sequence of construction [of different identities] is contingent on the social and political circumstances in which the individual grows up. …. A political identity … will include, inter alia, aspects of identity theta relate to particular geographical localities (such as municipalities, nations and regions), as well as aspects that relate to membership of a particular social group that may act politically (a socio-economic class, a linguistic group, or a particular ethnicity. These will frequently overlap.”( p 2)

We give an example of a bilingual Turkish/German origin 13 year old girl having many reference groups for her identities: “each of these reference groups brings with it different sets of duties and obligations, and different definitions of whom she will include in the reference group, and who falls outside it. She will expect different rights from the various groups and from the individuals in those groups, and she will expect different degrees of participation in decision-making processes in each setting. She will inevitably find some of these demands are sometimes incompatible, and will have to give priority, in a particular setting, to acting one way or another: she will live contingently.” pp 4-5)

Ross, A. (2003) Children's political learning: Concept-based approaches versus issues-based approaches. In C. Roland Levy and A. Ross (Eds.), Political Learning and Citizenship in Europe, pp 17-33. Stoke on Trent: Trentham

This chapter explores the development o political education in the UK curriculum, and then the citizenship education in the UK and Europe in the 1997-2003 period. This is set in a discussion about the relative merits of a concept-bases curriculum and an issues-based curriculum; a “delicate balance” (p. 29) is suggested.

“a variety of elements [must be] present: experiences, issues, concepts and structures and processes. … All of these are necessary components – not a single one can be left out- and the sequence is critical” (p 30)

“if we are to get away from safe teaching about structures and processes, about the neutral and the bland, then we need to ensure teachers re equipped with a wide conceptual understanding, with a knowledge of the issues that might illustrate these, and with the skills to manage covering the issues of participatory democracy through handling classroom political debate.” (pp 32-33)

Ross, A. and Dooly, M. (2010). Young people’s intentions about their political activities. Citizenship Teaching and Learning, 6 (1), 43-60.

Findings from a survey of 11-17 year olds in in Poland, Spain, Turkey and the UK that sought to explore the reality of the supposed ‘democratic deficit’ of young people. We suggest that young people behave very similarly to adults in how they define their political activities and expectations, and discuss possible educational responses to the intentions they describe.

“There is considerable political interest among young people in these four countries – though not necessarily political interest in the conventional sense of traditional party political activity.” (p. 56)

“Males seemed somewhat more inclined than females to participate in ‘conventional [political] activities’, and females to be involved in less conventional activities. Young people have always been more involved in direct, issues-focused political action that their elders.” (p.57)

2010 2011 2012

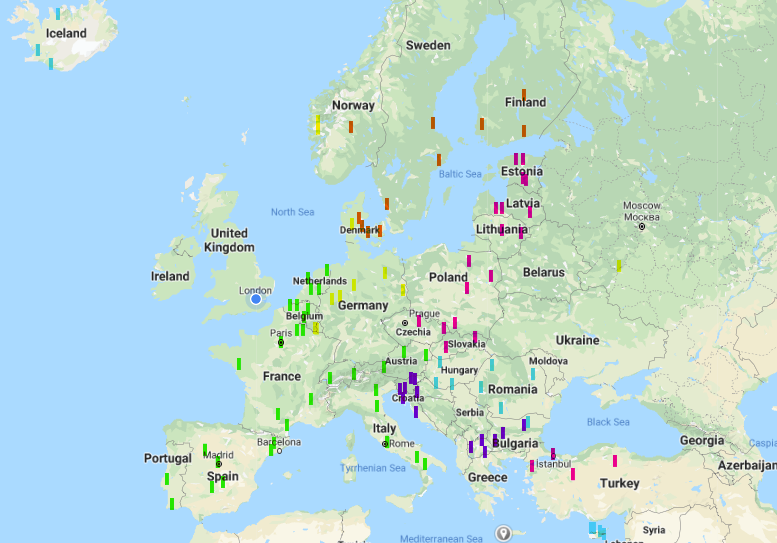

In total, I visited 49 different location, talking with 974 young people from 97 different schools and colleges, in 159 groups.

My findings were reported variously at a number of conference and lectures, and in some journal articles, and in full in a book: Understanding the Construction of New Young Europeans: Kaleidoscopic Identities (Routledge, 2015). These are all listed, with some extracts on Political Identities: details.

Phase 2 - western Europe, 2014 - 6

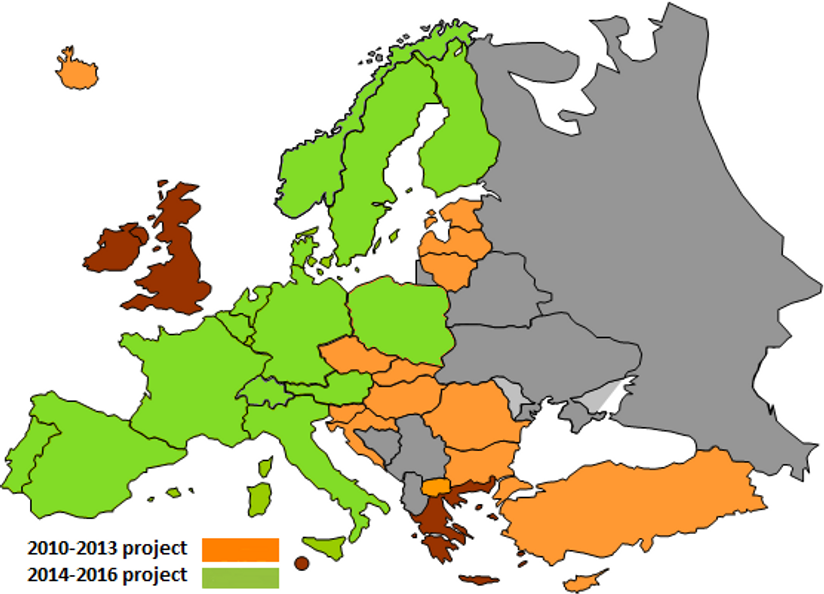

In 2014 I decided to extend the study to include the counties of western Europe, in particular those pre-2004 EU members (and also the associated states of Norway and Switzerland). However, my experiences in Phase 1 suggested that where there were particularly acute conditions related to EU membership, any discussions about ‘feeling European’ would be dominated by these conditions. In the 2014 context, I decided to exclude Greece, where the post 2008 bailouts to the economy were creating considerable concern and debate, and the UK, where there was in 2014 a real prospect of a referendum on continuing membership of the EU, generating much heat. By mid 2015 this was being planned (but all my fieldwork was completed before the referendum took place). In the context of the relationship between the Republic of Ireland and the UK province of Northern Ireland, I also thought it important that, in any study of political identity on the island, it should be made clear that the research was being conducted on both sides of the border. Thus Greece, the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom were not included in this phase, with the intention to return to them in less contentious times.

Phase 2 thus encompassed Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. Fieldwork was carried out between September 2014 and February 2016.

2014 2015 2016

In total in phase 2 I visited 55 different locations, talking with 1,024 young people from 85 different schools and colleges, in 165 groups.

A second book – Finding Political Identities: Young people in a changing Europe was published in 2019 (Palgrave Macmillan): this incorporated many elements of Phase 1, as well as all the data from phase 2.

Young People's Political Identities: Future plans

I have been planning to continue this study into other parts of Europe, but the COVI-19 pandemic has caused some disruptions, and there is some uncertainty about the immediate future. Changes and developments will be reported here. There are three potential areas of interest.

Eastern Europe

The states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia Moldova and Ukraine were part of a programme I developed with a group of civil society associations from these countries. In October 2019 I spoke at a meeting of the East European Network for Citizenship Education (EENCE) at their conference in Batumi, Georgia. Plans were made for a study of young people in these states to start in September 2020: these are now on hold. An investigation is being made into the possibility of on-line discussions. These countries are of particular interests because of the complex constructions of citizenship and nationality that were developed in the USSR, of which these six countries were once a part.

The Balkan States

While I visited some Balkan states in Phase 1, there remains Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Greece, Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia to investigate (and probably some updating on Bulgaria, Croatia and Macedonia). This area is importnat to study, because of the complex and fractured identities that followed the break up of Yugoslavia, and earliet than that, the break up of the Ottoman Empire. It is unlikely that I'll be able to tackle this area without collaborating with other academics, particularly to collect the empirical data that would be needed.

The Atlantic Islands

The UK and the Republic of Northern Ireland remain to be covered, and the political focus is still on the Brexit arrangements. Although they are currently at the end of the list, I don’t imagine the situation will be calmer till at least 2022/3. But by then it may be possible to make a detailed study.

Political Identities of Young Europeans: a summary of the findings

Young Identities in the Baltic (January 2011) | |

Young Identities in Turkey (June 2011) | |

Young Identities in Poland, the Czech republic, Slovakia and Poland ( 26 October 2011) | |

Young Identities in Cyprus and Iceland (12 January 2012) | |

Changing constructions of identities by young people in Romania (20 June 2012) | |

Changing constructions of identities by young people in Bulgaria (11 December 2012) | |

Changing constructions of identities by young people in Slovenia (23 May 2013) | |

Balkan and European - Young people’s constructions of identities in Croatia (23 July 2013) | |

Macedonian Young People: Constructing Identities in a Contested Country (25 March 2014) | |

Kaleidoscopic Identities: Young people constructing identities in the New Europe (2 June 2014) | |

Phase 2: Scandinavia (January 2015) | |

This is a qualitative investigation into how young people (aged between 11 and 19) are constructing their personal identities, and becoming aware of their actual or potential European citizenship. It focused so far on two groups of countries: the candidate states of Turkey, Croatia, Iceland and FYR of Macedonia, and countries that have joined the Union since 2004 - (the ‘Baltic States’ (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), the ‘Visegrad States’ (Hungary, Czech Rep, Slovakia, Poland), the ‘Black Sea’ states of Romania and Bulgaria; and Cyprus. (Croatia became a member of the EU during the study, in 2013.)

This map shows these countries in orange. The countries in green are the subject of my 2014-16 study).

The project took place between 2010 and 2013. My travel and subsistence costs were supported by the funding of my Jean Monnet Professorship. I am grateful for the European Commiussion's support through this award. Fieldwork took place between January 2010 and November 2012.

In all, I spoke with 974 young people, in 160 focus groups in 97 different schools in 49 locations across these countries. These discussions form the empiric basis of this study.

The principal account of the project is published as a book: Constructions of Identities by Young New Europeans: Kaleidoscopic Selves, published by Routledge (July 2014).

**********

On this page:

- An overview of the research

What I did in each city or town

- A summary of my principoal findings

- Further information and dissemination

Publications

Book

Articles and chapters

Round tables

London Metropolitan lecture series (with video links)

- Thanks to ....

*********

An overview of the research

I conducted focus groups with small groups of school students about their perceptions and views. These young people are at the ‘border crossing’ of Europe, and their perceptions – and that of those who teach them – are of particular interest and importance. What is their image of Europe in relation to themselves and their future? How do their teachers recognise this, and how those responsible for teacher education?

Social identities are increasingly recognised as being both multiple and constructed contingently within a context that includes the idea of Europe. Young people are developing identities that may include a range of intersecting dimensions, including gender, age, region and European. A growing number of young people in parts of the European Union are acknowledging an at least partial sense of European identity alongside their national identity: the degree to which this is acknowledged varies by nationality, gender and social class, as well as by age.

European integration depends on the development of a shared construction of at least some elements of Europe, and this is particularly true of these particular young people. It may be a shared conception of a Europe of differences, or a conception of the Europe as seeing its fractured past as ‘the other’, or of an emergent shared youth culture. Understanding how new young Europeans construct their idea of Europe, their role in it, and what it means to be European is of value and importance to a very wide audience.

What I did in each city or town

In each location, I worked with two schools, and in each school I talked with a group of about six 12-13 year olds, and a similar group of 15 to 16 year olds. I was not looking for the ‘best’ or the ‘worst’ schools, or ones that are unusually specialist. As there were two schools in each location, I tried to ensure that they represent different social areas or groups in the city or town.

Which young people? I was not trying to make a representative sample, but to look at the diversity of views. But I aimed at an approximate balance of male and female students. I was not concerned with legal nationality or status, but young people whose home is now in the country (so if there were significant minorities or migrants, I tried include a number). In all these visits, I was accompanied by a University/College colleague who acted as an interpreter for the discussions when necessary, and who discussed fine points of meaning with me.

I used focus groups, rather than discussions or interviews for this project. The purpose of the focus group was to let the participants discuss ideas, as far as possible letting them start with the vocabulary and expressions that they bring to the group, rather than ‘supplying’ words and concepts that may make them focus in ways that they would not otherwise do.

A summary of my principal findings

Each young person advanced a diversity of identities, changing over the course of each conversation: identities were contingently performed, according to the context of the particular discussion, the historical moment and the specific audience. While there was certainly fluidity in this, to describe identities as liquid, as Bauman has done (2000), is to suggest amorphousness: it implies that the identities constructed were shapeless, subject to physical laws of fluidity, merely filling the available spaces – and it denies agency. Despite the flexibility and acrobatic twists, there were patterns in what was said.

The metaphor that I would offer for the process of constructing identities is that of the kaleidoscope. Each individual used a palette of materials, configured in patterns that change as though one is looking through a lens or a filter: light is refracted and reflected in patterns that may be symmetrical, varying as the configuration of the mirrors. At different moments and contexts, the individual’s pattern changed - but it remained constructed from the same basic range, some materials more prominent in some patterns, obscured in others. What is seen - the momentary, situational, observer-dependent pattern of identities - is contextually contingent on the lens of circumstance, the audience’s perspective, the culture, the moment of discourse.

How do these young people differ? Differ as being ‘new’ Europeans in these countries, or in being a new generation, the post 1989 cohort? My argument has a number of elements.

Firstly, aspects of these countries’ status (newly joined, or potentially joiners) of the European Union encourages citizens and residents to reflect on their national or country affiliations, and the nature of their feeling of being part of the European Union. Identities are reconfigured to include new dimensions and relationships, particularly among this generation.

Secondly, the historical nature of many of these countries leads to particular potential for seeking to be European, being part of western European economy and culture. Both the pre-1945 experience, and surviving the events of 1945-89, have brought most of these countries a shared sense of being denied what they see as the political and economic advantages enjoyed by western European countries from 1945.

These two elements create a consensus and synchronisation: their emergence, post 1989, as independent countries has led them to look westwards to the European Union, and there is a corresponding trend in the identities constructed by these young people.

A third element is that these young people, born post-1989, only have vicarious memories of the first two. The combination of experiences – EU membership, soviet domination and the break of 1989 - have led most young people towards two conclusions. Firstly, they have a strong and sympathetic sense of why their parents’ and grandparents’ acted as they did, and why these earlier generations constructed the post 1989 states in which they now live; but secondly, they are liberated from the fears, memories and antagonisms that shaped the political orientations of earlier generations.

Their country was constructed, considered in isolation, in positive cultural terms. There was appreciation of the heritage, the language, and the cultural practices of the people, and the natural assets of the country. There were some reservations about the behaviours of some fellow country-people - often described as their ‘mentality’ - and this was particular evident in the constructions of a ‘balkan mentality’. There was generally a less positive attitude towards the civic elements of the country, and politicians’ behaviour often detracted from identification with the country. This feelings in some of disempowerment and a lacking of agency, and in others a desire to take action - or rather, to take action when adult - to change the situation.

These created a sense of benign patriotic affection for their country: a broad cultural affinity rather than a passionate commitment. This became particularly apparent when they discussed how they felt that their parents and grandparents identified with their country. Older generations, they felt, had a more nationalistic identification, which they frequently ascribed to the older generations’ experiences of the second world war and the communist periods, and the struggles to maintain national identity. There appeared - from the young people’s perspectives of their own identities - to have been a generational shift.

Identification with the country was modified when they began to compare their position with other states, particularly to countries that they thought had alternative civic structures and processes. Russia, the Ukraine and Belarus were constructed as being politically different from their country: this was the point at which political rights and freedoms were foregrounded, and their own country’s civic institutions were perceived more positively. Enthusiasm for the civic waxed and waned as the lens changed.

Europe, on the other hand, looked at from within, was largely constructed positively in terms of its civic institutions and practices. This was seen both at the personal and instrumental level - the freedom of movement - and at the level of economic and political support. Enthusiasm for the political support of the European Union was expressed sometimes as a bulwark against perceived threats, or as a buttress for democratic processes, or as promoting human rights. These civic features led them to modify their earlier comments on their country’s political practices, recasting them more favourably in the context of Europe. There was much less certainty about European culture: in every country there were some expressions of being excluded from European culture, or even whether European culture could be said to exist. It was very hard for most to pin down any specific characteristics of Europe with which to identify: the real Europe, if it existed at all, lay to the west. There were also concern that a European culture threatened their own country’s culture. But European culture sometimes emerged when other cultures were defined as non-European, as inappropriate for EU membership.

Young people felt that older generations’ views of European identities were constructed within their perceptions of national identity. Many young people saw their parents’ and grandparents’ identities as constructed by their lived historical experiences of conflict, war and antagonism, which supported both their more nationalist perspective and their sense of distance from being truly European. Many contrasted this with their own sense of being ‘true Europeans’: making a contrast with another generation shifted and strengthened their sense of European-ness.

These young people are adept at managing identities, drawing on sources not limited to the accounts of the school curriculum or of the family. They call on media, including social media, to illustrate and support their constructions, in a way that is sophisticated and global. They construct themselves as different from their parents, with different horizons and landscapes, and alternative narratives of the past. An important part of this process of differentiation appears to be a different sense of ‘being European’, which they are able to combine with a continuing sense of affection for their country.

Further information and dissemination

I have conducted round table discussions with my collaborators in these countries, and given lectures - a series in London at my University and elsewhere, and published papers and chapters as well as the Routledge book.

Publications

Books:

Constructions of Identities by Young New Europeans: Kaleidoscopic Selves, London: Routledge (July 2014).

Finfing Political Identities: Young people in a changing Europe: Palgrave Macmillan (2019)

Articles and chapters:

Border Crossings: Young Peoples’ Identities in a Time of Change 1 - The Baltic States and Turkey (2010) in P. Cunningham & N. Fretwell (eds), Lifelong Learning and Active Citizenship. London: CiCe https://metranet.londonmet.ac.uk/fms/MRSite/Research/cice/pubs/2010/2010_189.pdf

Border Crossings: Young Peoples’ Identities in a Time of Change in Claudiu Mesaroş (ed) (2011) Knowledge Communication: Transparency, Democracy, Global Governance. Timisoara: West University of Timisoara, pp 65-82

(With V Zuzeviciute) Border Crossings, moving borders: young people’s constructions of identitries in Lithuania in the early 21st Century. (2011) Profesinis Rengimas: Tyrimai ir Realijos, 20 (Kaunus, Lithuania) 38 – 47

Moving borders, crossing boundaries: Young peoples’ identities in a time of change 2 - Central Europe: Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia (2011) in P. Cunningham & N. Fretwell, Europe's Future: Citizenship in a Changing World: London: CiCe https://metranet.londonmet.ac.uk/fms/MRSite/Research/cice/pubs/2011/2011_130.pdf

Communities and Others: Young Peoples’ Constructions of Identities and Citizenship in the Baltic Countries. (2012) Journal of Social Science Education, 11, 3, 22-42

Controversies and Generational Differences: Young People’s Identities in Some European States. (2012) Educational. Sciences 2 2 pp 91-104; doi: 10.3390/educsci2020091

Ross, A., Issa, T., Philippou, S. & Aðalbjarnardóttir, S. (2012) Moving borders, crossing boundaries: young people’s identities in a time of change 3: constructing identities in European islands - Cyprus and Iceland in P. Cunningham & N. Fretwell (eds.) Creating Communities: Local, National and Global. London: CiCe https://metranet.londonmet.ac.uk/fms/MRSite/Research/cice/pubs/2012/2012_480.pdf

Identities and Diversities among Young Europeans: Some examples from the eastern borders. In Gonsalves, S. and Carpenter, M. (eds) (2013) Diversity, Intercultural Encounters and Education. London: Routledge, pp 141-163

Young Europeans’ constructions of identity in the new countries of Europe. (2013) European Civil Society Platform on Lifelong Learning (EUCIS-LLL) Magazine. 2. pp 10 -12 (also at http://www.eucis-lll.eu/eucis-lll/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/LLL-MAG2-EUCIS-LLL2.pdf

Intersecting identities: young people’s constructions of identity in south-east Europe London: Cice: Proceedings of the 15th CiCe Annual Conference (2013) (publication awaited)

Intersecting identities: young people’s constructions of identity in south-east Europe, in Uvanney Maylor and Kalwant Bohpal (2014) (eds) Educational Inequalities: Difference and Diversity in Schools and Higher Education. London: Routledge

Moving borders, crossing boundaries: Young peoples’ identities in a time of change 5: Constructing identities in some former Yugoslav States: Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia (May 2014): Proceedings of the 16th CiCe Annual Conference, forthcoming

Round tables:

Discussions with academics in each region:

Riga (December 2010): Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania

Plzen (September 2011): Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary

Watch this on video:

(part 1) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-JmpH_aLrkA

(part 2) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-aaGZOncGNw

Girne (May 2011) Turkey

Bucharest (June 2013) Bulgaria, Romania

Imagining and constructing intersecting Balkan identities: young people’s constructions of identity in Romania and Bulgaria. Keynote to the Eurofringes. Intercultural networking strategies Conference,. Bucharest, Romania

London Metropolitan Lecture Series ('Jean Monnet Lectures')

Young Europeans’ Political Identities: an overview

I’d been thinking about the idea of this project since the late 1990s: how do young people in Europe (between the ages of about 12 and 19) construct their political identities? How do they see themselves as being part of, and perhaps participating, in the politics and societies of their locality, of their country, of Europe, and perhaps globally? My general observations and discussions with young people led me to think that most young people of these ages were giving thought to this, but much political science literature, and general public discourse, suggested that young people were apathetic and uninterested in politics. I thought that these beliefs appeared often to be based on questionnaires and polling, and on quantitative studies that presented categories and concepts that tended to alienate young people, and that a much less structured qualitative study might produce rather different results. And I remembered when I was this age, and younger, being given the distinct lesson by adults that having an interest in politics was something that I shouldn’t express at that age – I was too young and immature, too open to being indoctrinated. I disagreed, but ‘learned’ not to say so!

My opportunity to investigate this in depth occurred when I decided in late 2009 to take slightly early retirement from my full-time work at the University, which coincided with the award of a Jean Monnet professorship, in recognition of my leadership of the European Commission CiCe Academic Network, that linked studies in a number of European universities of citizenship education. The travel grant that came with this allowed me to visit nearly all the countries that had joined the European Union after 2004, and the then candidate countries – Phase 1 from 2010 to 2013. I then took off independently to visit most of the countries that had been EU members before 2004 (and Norway and Switzerland) – Phase 2, from 2014 to 2017. Each of these phases is described briefly below, and in more detail on the page PI:details. The project is ongoing, and late on this page you’ll find details of my aspiration to continue my study in eastern Europe, in the Balkans, and in the Uk and Ireland.

Phase 1 - central Europe, 2010-14

My initial area of investigation was into the post-2004 EU countries, and to the countries that were then applying to join the EU (though this group has changed since then):

EU members 2004 – 2010: Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Cyprus (both the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus)

Candidate countries in 2010: Croatia (which became a member in 2014, after my fieldwork), Iceland, Macedonia (FYROM/North Macedonia) and Turkey

Most of the former group had previously been either members of the Warsaw Pact or part of the former USSR: they had all since 1989-92 become independent of Soviet Russian influence and hegemony. This meant that all the young people in my age group had been born and grown up after this – they were the first generation in these countries never to have known directly what life was like in those situations. Did this make them a different generation?

My technique was to use deliberative discussion techniques with small groups, of about six young people at a time. I used by contacts in each country to arrange to visit a number of different locations in each country, and a number of different schools or colleges in each location (ideally, at least one in a middle class area, one in a working class area).

Conversations were usually in English, sometimes translated or partially translated. Fuller details are given in the Political Identities: details page.

This map shows where I went – the different colours show each year.